Preventing and Diagnosing Cracks in Kilnformed Glass

If you are working with kilnformed glass, you are familiar with this subject! There are several reasons that glass will crack, and when it happens it may take some detective work to figure out why it happened. The most common reasons are:

Thermal Shock

Annealing Cracks

Incompatibility Cracks

Restriction Cracks

Trauma

I think we can skip discussing Trauma any further. If you drop the glass, or drop something on your project, you know what happened, and how to prevent it!

But, the other four reasons can be mysterious, so I will discuss them here. The basic concepts discussed here will apply to any type of glass, but any mention of temperature is meant to apply to temperatures used for firing Bullseye COE90 Glass.

Thermal Shock

This happens if glass is heated or cooled too quickly. The glass cracks immediately when this occurs.

Thermal Shock When Heating: when glass is heated from room temperature up to fusing temperatures, the molecules gain energy and the glass expands. It is critical that the expansion is uniform throughout the piece during the temperature range where the glass is still rigid – which is below 1000F. In order to make this heating as uniform as possible glass kilns are constructed with the elements on the ceiling – since the glass to be heated is often a sheet or assembly of components laid out flat on the shelf (rather than vertically). By applying the heat from above (rather than from the sides) the entire project is receiving radiant heat fairly equally. However, the glass also has thickness – and it takes time for the energy the glass is receiving from the heated air in the kiln and the radiant heat from the elements, to penetrate below the surface of the glass. Therefore, the heating process needs to be done slowly. This is why we put the glass into a room temperature kiln, and slowly increase the temperature rather than preheating the kiln, as we do when baking in the kitchen. The speed of the initial increase in temperature depends largely on the thickness of the glass. If you heat too fast, the glass will crack. Once the glass has reached 1000F – there is no more danger of thermal shock, and you can increase the speed much faster. Also, if you are using a ceramic kiln (instead of a glass kiln) with elements on the sides you are at much greater risk of uneven heating and thermal shock.

Thermal Shock When Cooling: The same issues are in play when cooling the glass, except instead of expansion we are dealing with contraction. This is an issue when we are below the annealing point – and I will discuss annealing below. Suffice it to say, that cooling needs to be slow enough that the glass cools through and through in a homogeneous fashion.

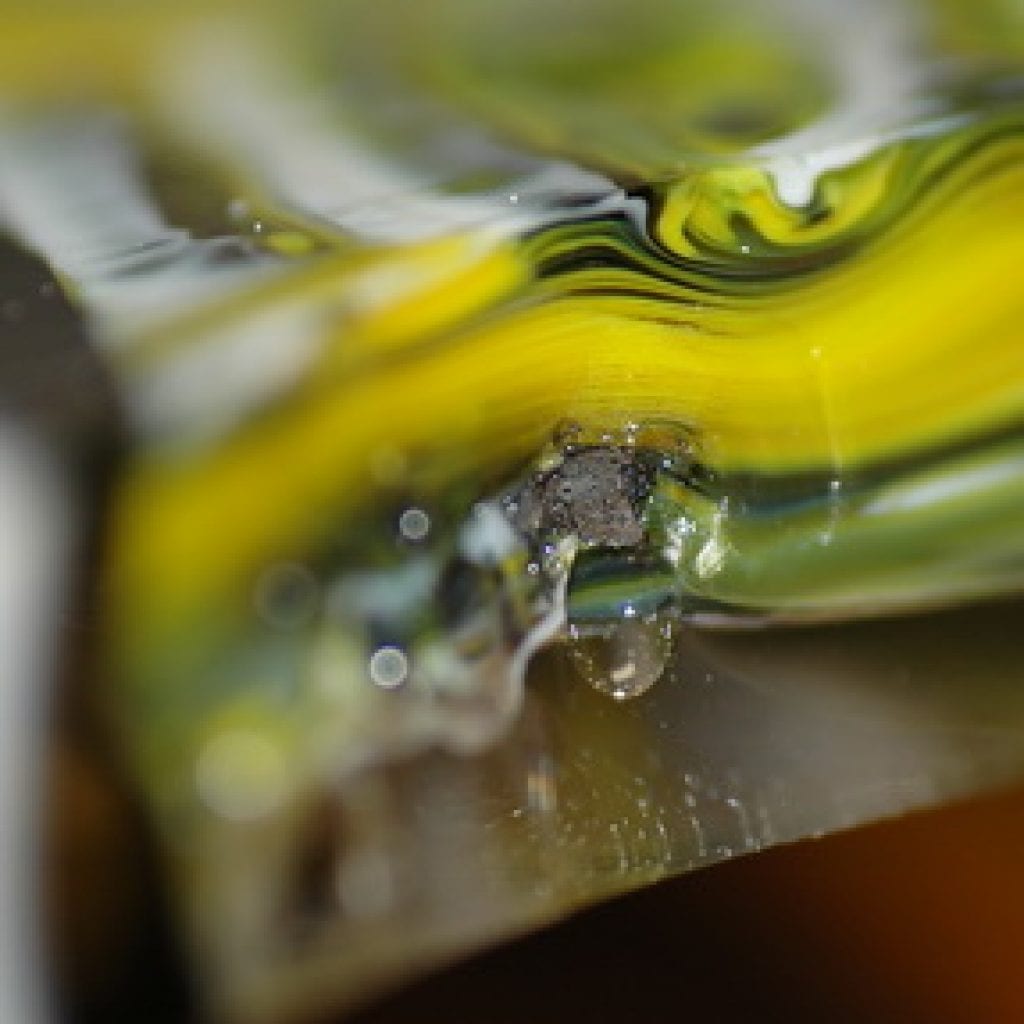

Note: you can also thermal shock glass when coldworking. If you do not have enough water to lubricate and cool your glass/abrasive interface – heat can build up and crack the glass.

Annealing Cracks

Glass is not a crystal. The molecules do not line up in a precise array, but rather in a random fashion. For this reason, glass is called an “amorphous solid”. As the glass goes from a high-energy molten state, to a low-energy rigid state, the molecules have to find a position, relative to their neighbors, that does not induce stress into the structure of the glass. If the glass is allowed to cool slowly enough, these molecules will find a nice, stress-free, arrangement. If the glass is cooled too quickly – stress will be introduced into the glass that will cause it to crack at some point in time. The solution is to follow the annealing schedules published by the manufacturers of compatible glass for kilnforming. Annealing usually takes place between 1000F and 800F. For Bullseye glass it is 900F.

Incompatibility Cracks

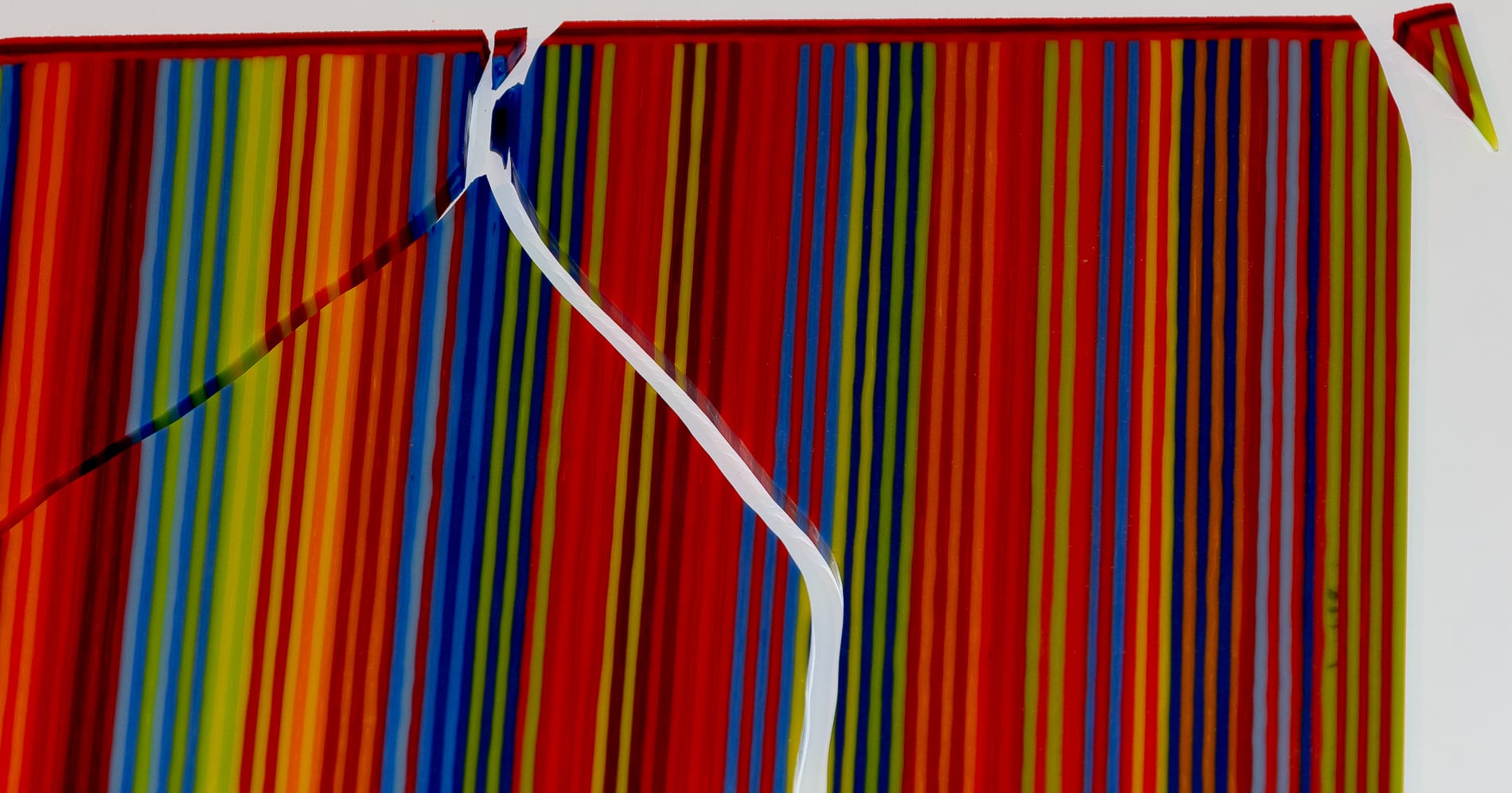

These cracks usually occur immediately upon cooling a fired piece, but it can also happen in the first few days, or upon refiring a fused piece.

The solution to this is to scrupulously make sure that you are only fusing together glasses that have been tested by the manufacturer and found to be “compatible for fusing”. Mixing brands with similar COE is possible – but not guaranteed to be successful. Alternatively, you can do your own testing by fusing the various glasses in question onto a clear reference sheet and using a polarized light to look for stress.

Bullseye glass is guaranteed compatible for three full fusing cycles to 1500F with 10 minute holds. With additional firings, or if you take the glass to a higher temperature, there is the possibility of a “compatibility shift” developing – such that the glass is no longer compatible. This is something to keep in mind if a project develops a compatibility crack after multiple firings. In general, with the exception of certain colors, I have found Bullseye glass to be very forgiving of multiple firings and high temperatures.

Foreign material

Another cause for a compatibility crack is foreign material within the glass. There are times when we want to place materials other than glass between the layers, such as wire, foil, metal leaf, etc. Some things work well, like copper. Others do not. It is also possible to accidentally have something end up in your glass. This can happen when doing an aperture pour (pot melt) if particles of the ceramic pot breaks off into the glass, or your accidentally drop your car keys into the pot.

Restriction Cracks

I’ve made this term up due to lack of established terminology – but this can happen if your molten glass sticks to something and is unable to separate as it cools. This is most likely to happen with an improperly prepared kiln shelf, but can also happen if the glass contacts any dams you have created to constrain the shape of your project. The prevention is to make sure that your shelf is newly and properly coated before each firing, and that all dams are covered with kilnwash – even if you have them separated from the glass with fiber. You never know when the fiber will pull away, or the glass will escape above or below it.

Diagnosis

With careful inspection you can usually figure out what has happened.

If the crack is a gentle curve or “S” shaped, and comes all the way to the edge of the glass, it is usually from improper annealing. If this happens, you can re-assemble the piece (if possible) and re-fire with an appropriate annealing schedule.

If the crack is along the junction of two specific colors of glass – suspect incompatibility, especially if the crack does not come all the way to the edge of the glass. If you re-fire this, the crack will usually come back.

If the glass is stuck to the shelf or a dam – it is from restriction of the glass, these cracks usually emanate from the point of attachment and may not go all the way through the glass. Glass fragments will remain on the shelf or dam.

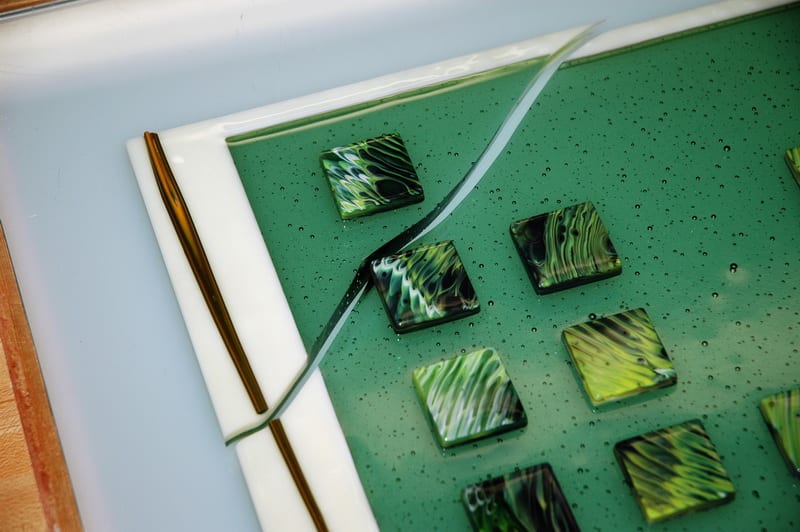

If the glass has cracked, but the pieces have soft, fused edges – it thermal shocked upon initial heating, and then went through the fusing cycle. (see image of round irid piece with crack that then fused).

If the glass has cracked into triangles with sharp edges – it thermal shocked on cooling.

If it doesn’t seem to fit any of these, check the edges of the glass for embedded foreign material.

If the crack occurs a long time after firing – it is probably improper annealing.

I hope you find this helpful, and that you rarely have to refer to this!

If you are a kiln glass artist, and are interested in one of the best and most cost effective methods of learning both basic and advanced techniques, the Bullseye Kiln-glass Education Online video lessons are fantastic. Click on this link to see the free ones, and consider signing up for the rest.